From XGBoost to Foundation Models: The Next Frontier in Fraud Detection

How financial foundation models could redefine risk modeling the way LLMs transformed NLP

It seems that fraud detection has changed little over the past decade: boosted trees, fed with loads of hand-crafted, high-signal features still reign supreme. But this may soon change, as a new wave of research aims to adapt the success of large foundation models from NLP to financial applications. Imagine LLMs, but trained on vast troves of financial transactions instead of text, and you get the idea.

The motivation behind this work is to not only break through the performance ceiling of XGBoost and its cousins, but also enable rapid onboarding of new tasks. For example, the same payments foundation model could be relatively easily fine-tuned for predicting fraud, abuse, credit default, future cashflow for customers, order volume for merchants, churn, or any other task that might emerge in the future, depending on business goals. Even without labels, pre-trained embeddings from a good foundation model alone may provide a sufficient starting point for zero-shot learning, at least in theory.

A notable recent breakthrough in this domain is Featurespace’s NPPR (Skalski et al 2024), a pioneering foundation model trained on Billions of actual transactions from 180 European banks, showing impressive zero-shot capabilities and significant performance improvements on previously unseen data. Let’s take a look.

NPPR architecture

NPPR is shorthand for the model’s training objective, which stands for:

NP = “next token prediction”: given the current token, predict the next token, and

PR = “past token reconstruction”: given the current token and a time delta δt, predict a past token that was seen δt seconds ago

In this context, a “token” refers to a payment event xt inside a single customer transaction time series, consisting of several numerical features (such as payment amount, customer age) and categorical features (such as merchant, category code, credit card issuer). Note that the event features do not include customer id itself because we don’t want the model to simply memorize a single customer’s transaction sequence, but instead to generalize across sequences.

Drawing the analogy to LLMs, a single customer transaction sequence is akin to a sentence, while a single transaction inside that time series is akin to a word or token.

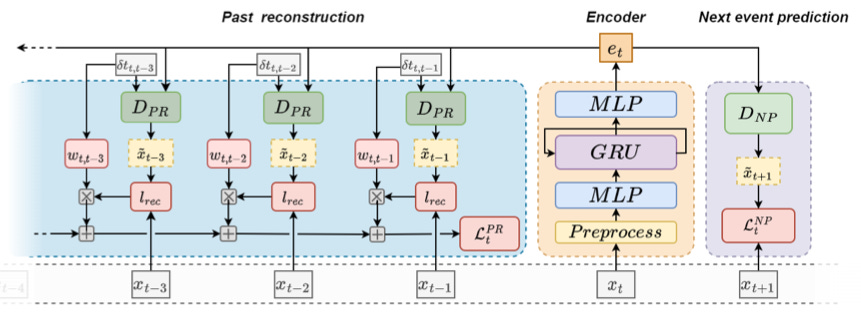

At a high level, NPPR is an encoder-decoder architecture with a single encoder and two decoders for NP and PR prediction, respectively. Let’s take a closer look at each of these modules next.

The encoder consists of a feature preprocessing layer (which normalized numerical features and one-hot encodes categorical features), an MLP layer, a GRU (Gated Recurring Unit, and another MLP layer that outputs a single embedding per transaction event. The reason of the use of GRU instead of a standard Transformer block is efficiency: GRU is light in FLOPs, latency, and memory usage, because — unlike self-attention — it doesn’t look at the entire sequence at once. Instead, it simply keeps rolling forward token by token, and learns contextual information in its hidden states. The trade-off is of course that GRUs are usually not good at learning long contexts. Hence the addition of the PR task, which forces the model to learn this long-context understanding via the loss definition and backprop.

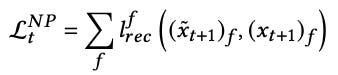

Both decoders are simply MLPs that take as input the encoder-generated event embedding and output a prediction, either of the next event (NP) or of a past event (PR). For the NP decoder, the loss is

where the sum runs over all event features, and the reconstruction loss lrec is the mean squared error for numeric features and binary cross-entropy for categorical features. For the PR decoder, the loss is

which is simply summing the reconstruction losses of the past (up to) K events, where the weights ω are given by an exponential decay function with the authors fine-tuned empirically to have a decay length of 2 months.

Results on public dataset

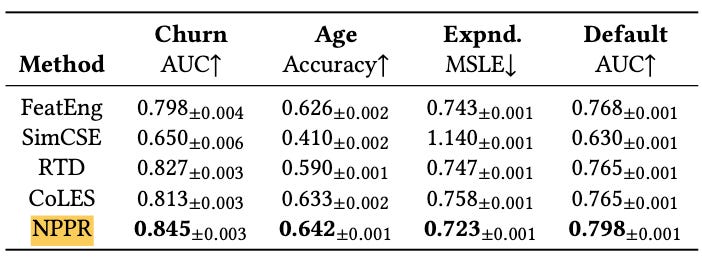

The authors benchmark NPPR on 4 public benchmark datasets consisting of customer churn prediction, future expense prediction, credit default prediction, and customer age prediction against 4 competing models:

SimCSE and CoLES, which are both contrastive learning approaches,

RED (Replaced Event Detection), which is an adaption of ELECTRA (a BERT variant),

a classical ML approach with hand-crafted features.

NPPR outperforms all 4 of these on all 4 datasets, for example yielding an +3% AUC lift over the best competitor (classical ML) on the credit default prediction dataset.

Result on real-world fraud detection

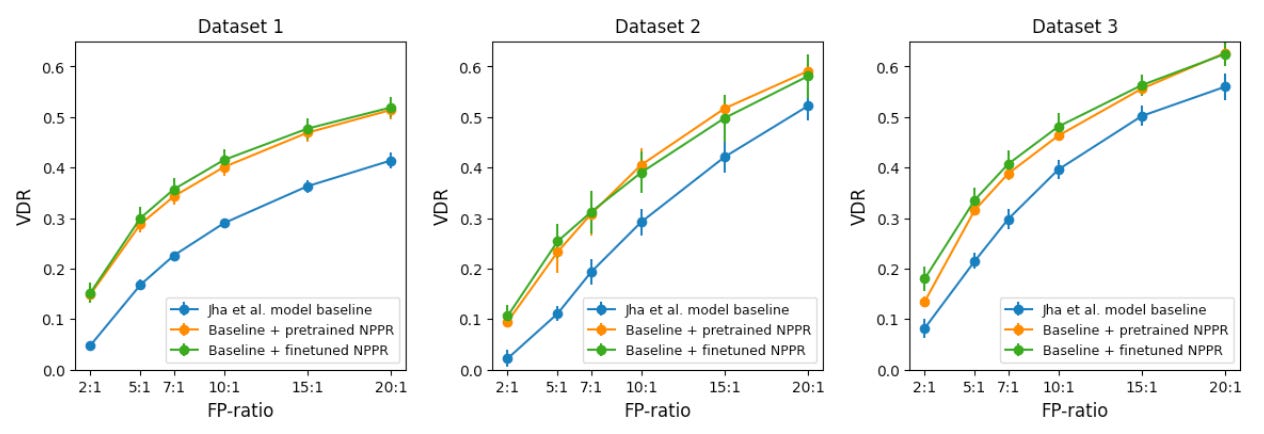

Public benchmark datasets are one thing, but professionals know that the real test is production data. Here is where things start to get interesting. The authors pre-train NPPR on 5B tokens from 180 EU banks / 60M credit card holders, and evaluate the model on fraud data from 3 banks that are not included in the pre-training set to see how well it generalizes to out-of-domain data.

The authors test 3 arms on this holdout set:

Baseline: A classical logistic regression model with hand-crafted features (Jha et al 2012),

Baseline + pretrained NPPR: Add pretrained NPPR embeddings as features into the model,

Baseline + finetuned NPPR: NPPR is further pretrained on the three holdout datasets, and these adapted embeddings are then added as features to the logistic regression. (The authors call this finetuning, though technically it appears closer to continued pretraining — true finetuning would introduce leakage.)

The metric measured is “VDR@FP”, or fraud value detection rate at false positive ratio — for example, “0.6@20:1” would mean that we capture 60% of fraud dollar value, while at the same time introducing 20 false declines for each true decline, a rather aggressive operating point (i.e. optimizing more for fraud capture than FPs).

The results are striking. Arm 2 consistently outperforms the baseline (Arm 1) by roughly 0.1 VDR across all FPR levels, indicating robust gains independent of the operating point. Even more noteworthy is that the gap between Arm 3 and Arm 2 is so small as to be practically undetectable. This suggests that a pretrained NPPR already functions effectively as a foundation model, demonstrating strong transferability to what the authors describe as “significantly out-of-domain data.”

Why NPPR matters

NPPR is notable as one of the first demonstrations of a financial foundation model with strong transferability and zero-shot performance—paralleling what we’ve seen in modern LLMs. That said, it remains early work, and there are several caveats worth highlighting:

Architecture: NPPR relies on GRUs rather than the now-standard Transformer blocks.

Training regime: No true fine-tuning was attempted. Instead, the authors use a feature-based approach, extracting NPPR embeddings and feeding them into a logistic regression model.

Baselines: The logistic regression baseline (Arm 1) feels like a strawman. A comparison against stronger baselines such as XGBoost or LightGBM would have been more convincing.

Looking ahead, I’d expect further gains and stronger transferability from modern techniques—e.g., Transformers (or HSTU variants), or the use of semantic IDs for high-cardinality categorical features such as merchant ids or merchant category codes.

Industry momentum and the road ahead

Based on public disclosures, several companies are already experimenting with financial foundation models for fraud detection and payments risk in production:

Stripe: Pre-trained a payments FM on tens of billions of transactions, improving detection of card-testing attacks from 59% → 97%.

WeChat Pay: Explored a Transformer-based payments FM. Their paper demonstrates a promising proof-of-concept, though lacks a baseline comparison.

Shopify: Invests in FM-based risk models, drawing on ideas from the Skalski et al. paper.

Broader research: More broadly, interest is also growing around foundation models for anomaly detection (e.g., Ren et al., 2025).

The key question is whether financial foundation models will move beyond prototypes and academic demos into production deployments—or whether they’ll remain largely theoretical. For now, only time will tell.